On the placement of the metaverse in the heavenly firmament

Is this 'metaverse' in the room with us right now?

Hello!

Since I last wrote to you (last week! imagine! two newsletters in as many weeks!) everyone has been talking about nothing but Elon Musk taking over Twitter. There’s plenty to say, and I’ve been tweeting about it if you’re desperate for my opinion. If you just want to follow me to a post-Twitter future, I’m on Mastodon.

But honestly I’ve spent enough time thinking about Twitter this week. Instead I want to talk about the metaverse, and ask a question: where exactly is it?

I don’t mean that in the sense of “where are the flying cars we were promised?” but more in the sense of “where is the train station?”. When we imagine things happening “in the metaverse”, where do we imagine them happening?

Way way back in the 90s, we called this stuff “cyberspace”. Everybody knew where cyberspace was—it was inside your computer, or maybe somebody else’s computer, or maybe in the mess of cables and stuff in between. When you entered cyberspace, you probably got sucked into the screen of your computer with one of those cool streaky early CGI effects. There was this other hidden world inside the mysterious beige boxes filled with strange components. Maybe you travelled like electricity along some neon-lit cables, a path of light through the darkness.

The “information superhighway” was in some senses a really weird metaphor, but it reflected a common understanding of how this stuff worked. The network of computers was like a road network: data went in at one end, moved along it, and emerged at the other end. If you could enter this “space” personally, it would be like passing through some sort of mysterious and shady underworld, filled with strange lights moving in every direction.

This idea of an underworld partly reflected the social understanding of computers at the time. Activity around computers, even when it was valued, was hidden away—basements and garages featured heavily in the description of the 90s computer nerd. The “hacker” archetype was a creature of both the figurative and literal underground. So it was natural to imagine the world they had created as a dark subterranean realm, full of incomprehensible mysteries.

The metaverse does not work like this.

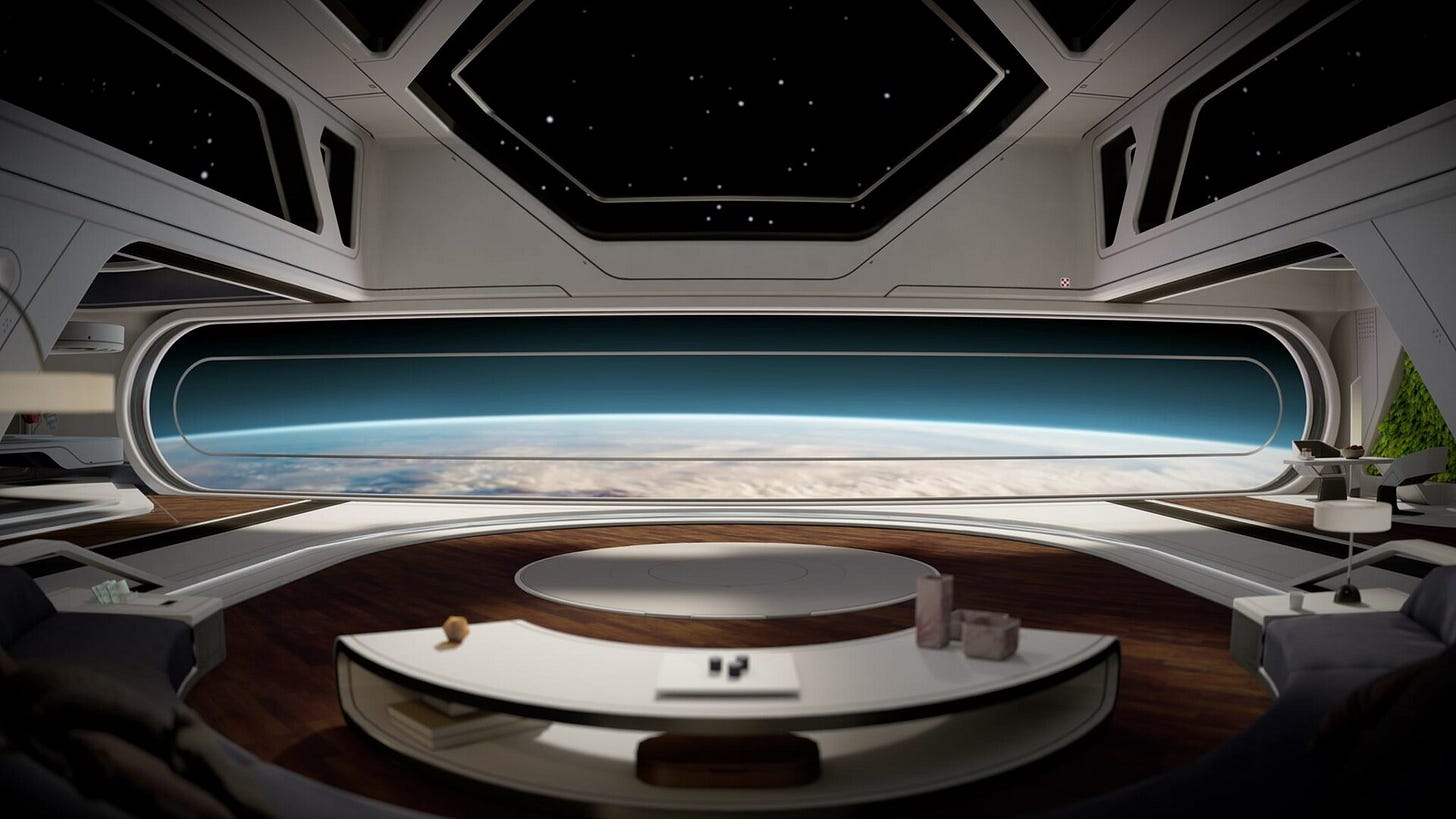

If we look at what’s being put out there by companies like Meta, we see a space that is bright and airy, a kind of electronic Disneyland. The strange abstractions of cyberspace have been replaced with cartoonish effigies of real-world spaces. This idealised reflection of our own world often centres on locations with a certain level of altitude: space stations, mountains, rooftops. The sense is of a world high above our own, rising above the dirt. Where cyberspace was subterranean, chthonic, the metaverse is rarefied, ethereal.

In part this reflects a change in the physical form of the technology. Big beige boxes and knots of cabling have been replaced by sleek reflective slabs and wireless connections. It’s a lot easier to imagine yourself being sucked into a computer if there’s actually space inside there. My phone is obviously too small to contain a whole world, so there has to be something else going on. That something else is “the cloud”, which hangs above us all.

It also obviously reflects a change in the (perceived) social status of the people pushing it. This is no longer a bunch of nerds in a basement—it’s Mark Zuckerberg, who could buy and sell all of us with the spare change in his pockets. His metaverse is aspirational, a reflection of an earthly paradise that people like him can actually live in, but which the rest of us can only experience vicariously through his company’s services.

So we’ve got a nice clean opposition: cyberspace is down, the metaverse is up. Very dialectic. But these two directions are not the-same-but-opposite. The earth and the sky might be mirror images in some sense, but we only live on one of them. The other is beautiful but inaccessible.

The key difference between these visions is that cyberspace was always seen as an adjunct, an alternative way of accessing the physical world. A hacker in a William Gibson novel might enter cyberspace in order to access new capabilities, but those capabilities were always directed at a change in the real world. The objects in cyberspace were representations of actual things, and anything that happens in the virtual realm has repercussions in the physical.

The metaverse, by contrast, seems to pride itself on being completely separate from physical reality. The shiny conference rooms and ski lodges are completely fictitious. Even if you are able to interact with them in some minimal way, they have no effect on anything in the real world. For the most part though, they’re background scenery.

So we have the eternal unchanging realm of the metaverse above, and the dynamic interconnected realm of cyberspace below. If you’re inclined to Christian metaphor, a division between the earthly sphere and the empyrean heaven (if you like this argument, grab a copy of Margaret Wertheim’s The Pearly Gates of Cyberspace).

Now we can obviously hold both of these ideas in our minds at once. Certainly there have always been those who thought of cyberspace as a glorious realm of pure information, unshackled by material concerns. But I think it’s noteworthy that as we’ve moved from a world where computers were a nerdy sideshow to something not too far from the corporate dystopias imagined by cyberpunk writers, the specific form of the virtual world fantasy has changed. Instead of imagining that computers could be a tool of empowerment, we’re left imagining them as an escape hatch, a fantasy of a fantasy.

So I guess what I’m saying is, bring back cyberspace. If nothing else, it had much better fashion sense.